This I Can’t Do

Harry Frankfurt, Hannah Arendt, and Immanuel Kant

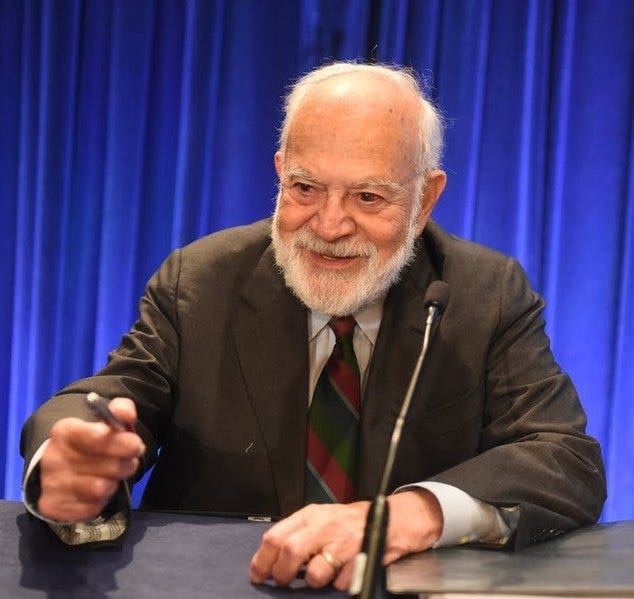

Frankfurt in the last essay of ‘The Importance of What We Care About’1 describes a person who reasons to themselves that they should perform some action, and then finds themselves unable to do it.

If he is nevertheless unable to act, because he finds the action unthinkable, then what keeps him from acting is a volitional matter. He cannot perform the action because he cannot will to perform it [181].

To Frankfurt, this “rationality that pertains to the will itself” [190] is an essential part of yourself, even though it is part that is hard to control or understand. Are you morally responsible for the good deeds you’ve done, if you can’t say why you’ve done them?

Arendt broaches the same subject in describing Germans who chose not to participate in the Nazi regime2:

If you examine the few, the very few, who in the moral collapse of Nazi Germany remained completely intact and free of all guilt, you will discover that they never went through anything like a great moral conflict or a crisis of conscience. They did not ponder the various issues… In other words, they did not feel an obligation but acted according to something which was self-evident to them even though it was no longer self-evident to those around them. Hence their conscience, if that it is what it was, had no obligatory character, it said, “This I can’t do,” rather than, “This I ought not to do.” [78]

Frankfurt supposes there are times when we do a good deed without knowing why - Arendt, supposes that all morality might be this way. Volitional limitations might be more fundamental to our morality than reason. Arendt references Kantian morality, characterizing it as a process by which reason determines the right course of action, and this determination creates an obligation on the will. Arendt’s argument above is partly that morality is not experienced as an obligation - a person’s morality is binding because it is perfectly self-evident to their will, rather than arising from a reasoned determination.

How would Kant see this, specifically in the ‘Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals’? To start with, take Kant’s statement of morality, the Categorical Imperative:

Act only on that maxim whereby thou canst at the same time will that it should become a universal law. [4:421]

Kant proposes the Categorical Imperative as a test where reason can determine if a maxim is good. An action that lacks moral worth is self-contradictory if applied universally. For example, lying is self-contradictory in the sense that if everyone lied, lying would not work, since nobody would believe each other. In this way, reason can arrive at moral truths without relying on an moral presuppositions.

It’s easy to doubt that this argument really works. One objection is that it seems too strong to say that this is a contradiction. We might easily say that the world where nobody believes each other would be worse, but that inserts a moral judgement, and defeats the goal of arriving at morality from non-moral reasoning. Other examples besides lying are even less clear - Kant claims universalized suicide is self-contradictory, but that’s certainly not obvious.

However, the primary test of morality is not what we can reason consistentlyy but we are “able to will”.

We must be able to will that a maxim of our action should be a universal law. [4:424, italics Kant’s]

Kant then distinguishes actions that “cannot without contradiction be even conceived as a universal law of nature” [4:424], like lying, from others:

In others this intrinsic impossibility is not found, but still it is impossible to will that their maxim should be raised to the universality of a law of nature, since such a will would contradict itself. [4:424]

Kant implies there are two senses in which contradiction is meant - in the first there is a conceptual contradiction and in the second a contradiction of the will with itself. In this second case, for an action to be immoral, it just needs to be one you couldn’t really will to be universal. Why would you be unable to will it so? Maybe the will has a “rationality that pertains to the will itself”.

When Kant tries to define a process by which reason can identify moral decisions, he still asks reason to consult the will. Kant seems to agree with Frankfurt that the things our will knows are essential. Or as Frankfurt puts it:

Logical necessities define what it is impossible for us to conceive. The necessities of the will concern what we are unable to bring ourselves to do. [190]

Frankfurt, ‘The Importance of What We Care About’, Cambridge University Press, 1998

Arendt, ‘Responsibility and Judgement’, Schocken Books, 2003