The Only Working Morality in Times of Crisis

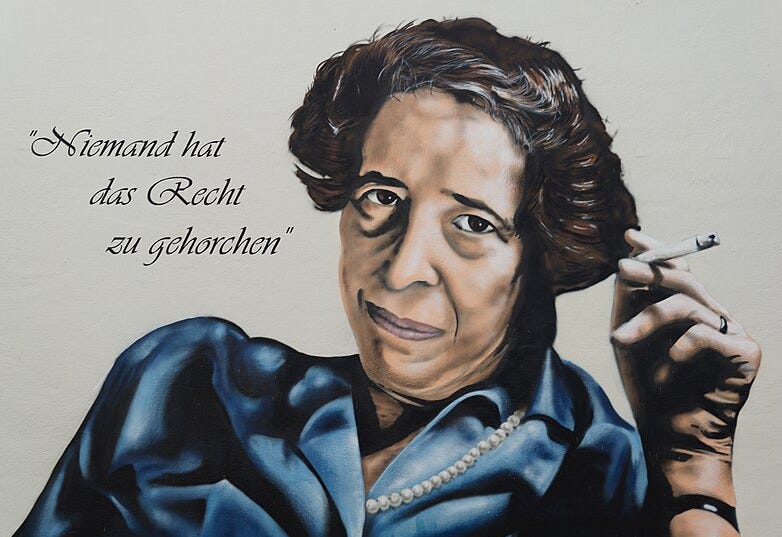

Arendt on morality

Today, I try to reconcile the different ways Arendt discusses morality. To start with, in ‘Some Questions of Moral Philosophy’, reflecting on Nazi Germany [p50,61], Arendt rejects an objective morality that is known to everyone:

This [moral] obligation, however, is by no means self-evident, and it has never been proved without stepping outside the range of rational discourse. [p77]

Instead, Arendt proposes a morality founded on community or intersubjectivity:

the question arises whether there is really nothing to hold onto when we are called upon to decide that this is right and that this is wrong… Yes- if we mean by it generally accepted standards as we have them in every community with regard to manners and conventions, that is, with regard to the mores of morality. [p143]

And yet, Arendt’s most memorable discussions of morality are personal. Arendt characterizes Eichmann’s evil as originating from a lack of thoughtfulness and refers to the argument from conscience given by Socrates in the ‘Gorgias’. These justifications are based on a lone thinker without the interference of others. Far from being dependent on community, they may put you at odds with the whole world1.

And yet, my friend, I would rather that my lyre should be inharmonious, and that there should be no music in the chorus which I provided; aye, or that the whole world should be at odds with me, and oppose me, rather than that I myself should be at odds with myself, and contradict myself.2

How do the personal and interpersonal justifications fit together? If all on my own, I can know the right thing to do and justify my motivation, why do I also need an interpersonal justification? And if I can’t determine what’s right on my own, why should I trust the judgement of others?

To quickly hash out some terms, the personal and interpersonal are paralleled by ‘thinking’ and ‘judging’. Roughly, by ‘thinking’ Arendt means forming general rules and ‘judging’ is applying those rules to particular cases [p143,p189]. Thinking is always solitary, whereas judging can be communal [p106] and is closer to the political (which is a major subject for Arendt I won’t get into here). It’s possible to imagine someone avoiding thinking, but very hard to avoid judging.

My opinion is that the two routes of justification are related, but accomplish different goals. The personal justification is the more certainly true, but with smaller reach. The interpersonal has broader reach, but is less certainly true.

I find the argument from conscience compelling because I’m pretty sure it’s true. Philosophy is hard. Sometimes the arguments are confusing. Arguments justifying why I should do the right thing can be particularly tricky (eg post on Kant). But I know that I have to live myself! Trying to avoid feeling bad is a very obvious way to justify my actions.

Does thinking on its own lead to moral truths? While Kant might think so, Arendt is reluctant to go that far (see post, Mahony p145). Arendt instead tries defend the more modest claim that thinking tends towards the better. This is hard to prove, and she may be presupposing more Kantianism than she admits. Personally, I personally feel comfortable claiming that your conscience is sufficient motivation and a sufficiently reliable guide.

Regardless, I can’t use the ‘argument from conscience’ on you. Eichmann doesn’t seem to have been troubled by his conscience and it seems doubtful that telling him he should feel badly would have been effective. When Socrates is arguing with Callicles, Socrates can only explain that it’s how “I” feel. Socrates at this point refers to Callicles in the third person, admitting that this argument won’t work on him and isn’t really directed at him (“Callicles will never be at one with himself, but that his whole life will be a discord.”) Arendt implies that if we can spur others to think (as Socrates does with other interlocutors), perhaps their consciences will weigh more on them, though there is obviously no guarantee.

What argument could we use on Eichmann or Callicles? We can try the interpersonal justification. Arendt argues that people live as members of communities and these communities share a ‘common sense’ of the more literal, Kantian flavor. Judgements, including those of morality, may be viewed as valid by individuals with a shared common sense.

The validity will reach as far as that community of which my common sense makes me a member [p140]

But you might object that Eichmann was a member of a community, one whose actions we find abhorrent. Why should we believe that interpersonal judgement will tend towards morality? Arendt’s answer is that communal judgements are conventional, but not arbitrary. Both the communal and personal justifications are grounded in the same thinking activity. Being a member of a community means being able to think from the point of view of other members of your community (reminiscent of recent Sellars post).

There is an obvious connection between thinking from the perspective of other members of your community and engaging with your conscience. Whether you’re arguing with your conscience or imagining yourself in your neighbor’s position, you are practicing what Kant called ‘enlarged thought’, which is one of the few reliable indicators of sound thinking [see Mahony p127]. The personal and interpersonal justifications share this same ground.

The validity of common sense grows out of intercourse with people - just as we say that thought grows out of the intercourse with myself. [p141]

More than just sharing a common ground, the interpersonal is the culmination of the personal. The inclination to think from other people’s perspective is fulfilled by a deeper engagement with others in order to more truly understand their perspective.

The upshot is that the interpersonal justification aspires to broader reach, though with less certainty. People who view themselves as members of a community will likely see the judgements of their community as validly applying to them. But the judgements may appear conventional, rather than self-evident, and historically have sometimes gone off the rails.

I think of the personal argument as minimal. It doesn’t get you very far, but it’s “the only working morality … in times of crisis and emergency” [p106]. Ideally, we’d avoid crisis and emergency. Perhaps more hopefully, we form communities that are compelled to think ever broader, and have the legitimacy to drag any thoughtless members along with us.

Recently read Mahony who is primarily interested in contrasting the Eichmann and Socrates framing. Mahony, Deirdre Lauren. Hannah Arendt’s Ethics. India, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

Plato’s ‘Gorgias’, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1672/1672-h/1672-h.htm